Kennecott’s permitted transportation route has ALWAYS been on existing roadways. Yes, they were pursuing a more direct route to their newly acquired processing site, (not part of the original permit) but were operating outside of the Mining Law, Part 632. The company wasn’t going to amend the permit unless they had a solid route in the bag. This process is backwards, as mining expert Jack Parker has stated repeatedly.

Kennecott’s plan is to truck tons of acid generating rock over our quaint county roads and through our suburban neighborhoods, profoundly impacting our health, safety and tourism-dependent communities. According to several regulatory agencies, the Woodland Road was not a viable solution to their transportation problems. It is the State of Michigan’s responsibility to revoke all mining permits and terminate construction of the mine until these problems can be resolved with appropriate public input.

The company was willing to invest $80 million in a doomed haul road, but refused to fund a $1.5 million hydrological study of the water rich Yellow Dog Plains region, or to complete a fully developed environmental impact study on the entire project (including the Humboldt Mill) and on any potential transportation route.

Kennecott’s implementation of Part 632 Mining Law has been an illegal fiasco from the start. They have arrogantly operated outside of the law for both the power lines and the transportation issue while the MIDEQ stands guard, allowing the company to potentially and immeasurably impact our local communities.

Save the Wild UP

Public Response to the Decision: http://www.miningjournal.net/page/content.detail/id/557966/More-objections-voiced-to-Kennecott-trucking-plan.html?nav=5006

CR 595 project abandoned

January 18, 2011 – By JOHN PEPIN Journal Staff Writer

ISHPEMING – After investing more than $8 million and nearly five years into developing a north-south haul route from its Eagle Mine, the Kennecott Eagle Minerals Co. has announced it will scuttle that effort and instead put money toward upgrading existing county roads for trucking ore to a processing facility in Humboldt Township.

The decision comes after a December meeting between representatives from the Marquette County Road Commission, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and Environment, Grand Rapids company King and MacGregor, which does environmental engineering for Kennecott, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

At that meeting at the DNRE offices at K.I. Sawyer, federal officials said prior wetlands destruction and other objections raised over a 22-mile road proposed in 2009 by Woodland Road LLC, which included Kennecott, remained in place for a revised project called County Road 595, which the road commission voted to pursue in October.

“We were optimistic that we could successfully develop a solution that would address Kennecott’s needs as well as long-standing community requests that Kennecott develop a route for our trucks, and lessen some traffic in and around the city of Marquette,” said Kennecott Eagle Minerals Acting Project Director Andrew Ware. “Unfortunately, due to environmental obstacles imposed by federal regulators coupled with the uncertain timelines and cost, we must move forward with the originally designated route, one we are committed to making work.”

Kennecott began work on surface facilities for the Eagle Mine in Michigamme Township in April. Construction is on schedule and is continuing through the winter, according to Matt Johnson, Kennecott manager of external affairs. The mine is expected to produce 300 million pounds of nickel, 250 million pounds of copper and trace amounts of other minerals.

“We need to make decisions today that the existing roadways will be ready when the Eagle Mine is in production, which would be in late 2013,” Johnson said.

The Woodland Road -which was to run from Marquette County Road AAA to U.S. 41, roughly one mile east of M-95- was expected to cost roughly $50 million and would have been paid for by Kennecott. The road would have taken two years to build, opening in 2013, with 125 jobs created during construction along with a dozen ongoing maintenance positions.

After that project was shelved last May because of federal objections, Kennecott said it would finance construction of Marquette County Road 595, which was estimated to cost between $50 million and $80 million. That road was slated to be laid out within a corridor eight miles wide. A final route was not determined.

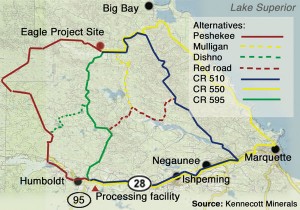

In its original plans for the mine, Kennecott planned to move ore from the mine east across County Road AAA to County Road 510, then south along County Road 550, through the city of Marquette to a railhead west of town.

Environmentalists and other Kennecott opponents objected to that plan and suggested a north-south route be developed. Later, when the Woodland Road and County Road 595 were proposed, opponent concerns were raised over the north-south route being developed in a largely undisturbed area.

Since its original plan was first proposed, Kennecott has decided to use the Humboldt Mill as a processing center. The company will now develop the original trucking route along those existing county roads from the original plan, but in Marquette will use Wright Street to U.S. 41 and then west to Humboldt.

“Any change to the original route would have to be amended (with the state),” Johnson said.

Kennecott explored the possibility of using other roads, including the Peshekee Grade and Marquette County Road 510, but those options didn’t pan out.

“Over the summer and this fall, we put extensive resources into mapping alternative routes,” Johnson said. “Other routes were deemed not prudent or feasible to construct in comparison to the County Road 595 corridor or existing roadways from the original plan.”

Kennecott plans to now begin working to determine what structural, environmental and safety improvements, including bridges and other stream crossings, will be needed along the route. The company plans to implement a development plan over the next several weeks, which will include discussions with residents.

“While we believe the proposed County Road 595 was a better solution, we are prepared to use existing truck routes county roads 510/550 as specified in permit conditions approved for the Eagle Mine,” Ware said. “Kennecott is committed to working with residents and to paying for necessary upgrades and significant safety and structural improvements to the Triple A, county roads 510 and 550, Wright Street, and other transportation infrastructure.”

Kennecott will begin immediately to work with local permitting authorities, residents and others in the community to solicit input on future plans for road improvements.

“We understand there will be questions that we need to answer,” Ware said. “We are prepared to listen, and do what we can to ensure the best possible solution.”

Johnson said the cost for the improvements has not been determined yet. The road commission would likely submit permits for the work, with final approval needed from the DNRE, Johnson said.

In its development of the Woodland Road and County Road 595, Kennecott invested more than $8 million to purchase property to enable development of the roads, as well as funding costs for environmental, engineering, alternatives analyses, and permitting studies.

John Pepin can be reached at 906-228-2500, ext. 206. His e-mail address is jpepin@miningjournal .net.

Letter to the Editor about Kennecott’s ramrodded power-to-the-mine project:

http://www.miningjournal.net/page/content.detail/id/557800/Mistakes-made.html?nav=5067