Marquette, MI — Concerned citizens are publishing the details of an underground collapse incident at Eagle Mine, citing grave concerns with the company’s lack of transparency. The revelations follow several “Eagle Mine Community Meetings” in which the company failed to disclose the details of a significant incident that happened in 2016.

“I attended Eagle Mine’s meeting anticipating some honest discussion of their 2016 underground collapse. Instead, they demonstrated how to use a virtual fire extinguisher to fight a virtual fire. Their 2016 safety review mentioned only medical incidents: a contractor who fell from a ladder and sprained an ankle, an employee who experienced a heart attack, etcetera. Eagle claims that ‘providing transparent information is important to the way we do business,’ but Eagle Mine’s behaviour is anything but transparent,” said Jeffery Loman, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community tribal member and former federal oil regulator.

“Representatives of Eagle Mine failed to address the collapse until they were asked by a concerned citizen at a community meeting in Big Bay, at which point they tried to claim it was an insignificant and harmless incident,” said Nathan Frischkorn, a resident of Marquette.

“Eagle Mine’s failure to disclose a serious underground collapse is outrageous, in light of their request for more permits to expand mining into the new Eagle East orebody. Permitting hinges on public accountability. At the same time, Eagle Mine wants to remove more ore from the very highest levels of the Eagle Mine – a move which experts have long warned could cause the mine’s ceiling or ‘Crown Pillar’ to cave in,” said Kathleen Heideman, Upper Peninsula Environmental Coalition (UPEC) board member and a member of the Mining Action Group.

RUMORS SURFACE

Rumors of the underground collapse at Eagle Mine first surfaced in fall of 2016, when a story circulated that some “mine contractors” had quit over an underground incident they felt was “dangerous.” Responding to the direct question “Was there a partial pillar collapse?” Eagle Mine confirmed that an incident had taken place, but did not use the term “collapse” and provided only a few details:

“In early August, there was a fall of ground incident that occurred during a routine blast in an active stope. The fall of ground occurred due to an unidentifiable natural horizontal feature that failed during a blast, causing a section of ore to fall. Eagle Mine safety standards require all employees to be on the surface during a blast, therefore no employees were underground or at risk at the time of the incident. The situation was identified by employees during the post-blast inspection. Eagle Mine notified the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) who conducted an investigation. MSHA notification is required whenever an unplanned fall of ground occurs at or above the anchorage zone in active workings where roof bolts are in use.”

Documents received in May of 2017 from the federal MSHA via a Freedom of Information (FOIA) request filed by a local concerned citizen make it clear: the unplanned “fall of ground” was a significant “large block failure.”

- Eagle Mine’s Wilhelm Greuer told the MSHA investigator, “this was a wake up call.”

- A large portion of an underground stope unexpectedly collapsed. The mining term used by the company is an “unexpected fall of ground.” It was described by MSHA inspector as a “substantial” event, and could have happened at any time.

- While it is true that no one was working in the drift below the stope when it collapsed, a crew of Cementation employees had been installing rock bolts into the stope prior to the collapse. It could have been a fatal accident.

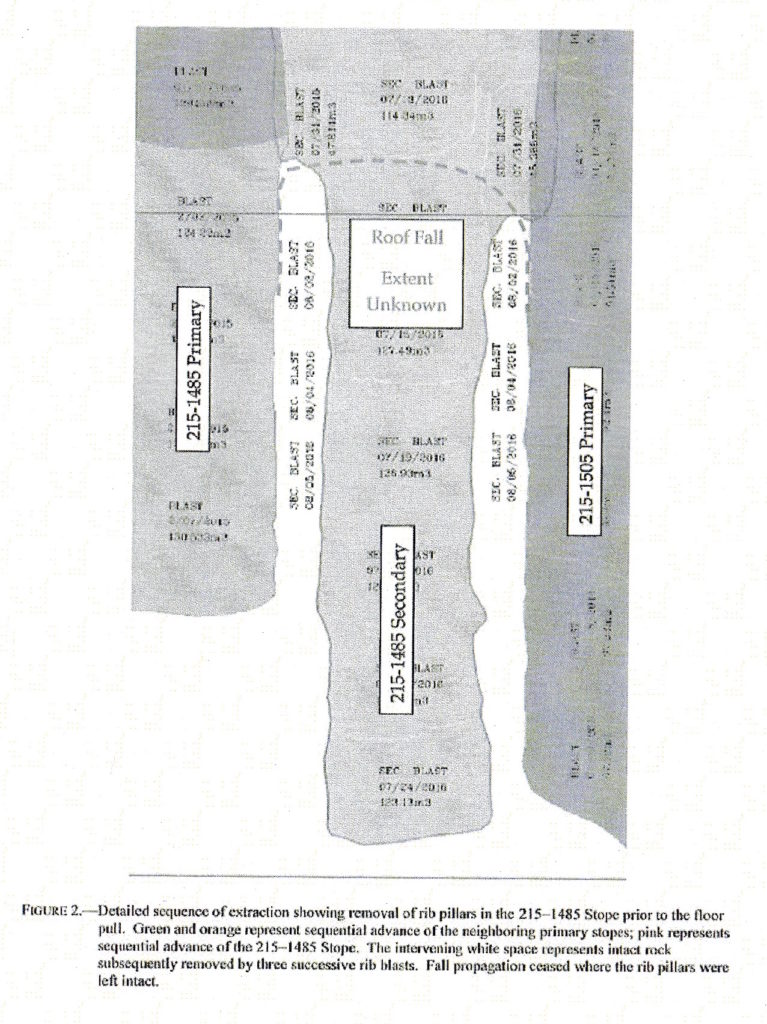

- The “unidentifiable natural horizontal feature that failed” (as described by Eagle Mine) was actually a fault, a critical fracture or flaw within the orebody. Was it truly unidentifiable – or simply unidentified? The geological fault or crack ran diagonally through stope 1485 on level 215, which is a “secondary” stope (unit or compartment of ore) contained between two primary stopes, which were already mined out and backfilled. A large quantity of ore below the fracture collapsed without warning. Mining experts describe these fractures as “rock discontinuities” and have warned that the Eagle orebody is filled with hard-to-map “smaller-scale discontinuities that could weaken the rock mass.”

- The blast that “triggered” the collapse actually took place elsewhere in the mine, in another stope. Eagle said the collapse took place in an “active” stope, but it was not targeted for blasting when it collapsed.

- The stope dimensions were approximately 33 feet wide by 80 feet high. A working access drift (tunnel) had been widened to the full width of the stope, further destabilizing the ore block. MSHA’s report states “the back broke approximately 9 meters (30 feet) above the existing 20 foot cable bolts.”

- According to the MSHA investigation, the bolts that were installed “represented approximately one-quarter of the capacity” that was actually necessary for supporting the ore block.

CONCLUSIONS

Alarmingly, MSHA concluded that “because the planar discontinuity (…) was unanticipated, and the failure block was too large to support with a reasonable bolting system, it must be assumed that similar discontinuities could be encountered, any time.” For greater stability, MSHA recommended leaving ribs of ore in place between stopes to increase safety: “rib pillars should be left in place in secondary stopes to provide physical, standing support.” According to Parker, this mining method was recommended from the beginning. Why was this common sense safety practice (leaving ribs for better support) not done? Simply put, the company did not want leave behind valuable ore. Full-stope mining means taking everything – leaving no ore behind.

While questions were raised about the integrity of cemented backfill, MSHA concluded “this event is not considered a backfill failure issue.” In the wake of the incident, however, several changes were made to Eagle Mine’s backfill regime: changing the cement recipe, heating water before adding it to cement, and even the method of cement placement. Edges of backfilled stopes were found to contain voids and loose material, which may have further contributed to the instability of the ore block.

It is not clear whether MSHA’s recommendations were suggestions or requirements, or whether Eagle Mine has modified their mining practices to avoid future unexpected collapses.

“Criminally defective decisions made by the Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources and Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) caused the permit to be issued despite obvious and serious legal and technical shortcomings. Eagle Mine’s permits were built upon false design and false data provided by amateur consultants who blatantly fabricated numbers, maps and sections which are in no way representative of the conditions in and around the orebody. The mine owners and their consultants still share responsibility for these errors, some of them life-threatening, all of them jail-worthy,” said Jack Parker, a veteran miner and mining consultant.

“Lundin and the Eagle Mine management have demonstrated to the general public what we have known all along: they will withhold information from the public if it might be damaging to their image. Lundin could have disclosed this information at the Eagle Mine forums held last fall or last week. They chose not to,” said Gene Champagne of Concerned Citizens of Big Bay.

“It is incomprehensible why Lundin would widen the access drift below the stope without providing additional support. The MSHA report indicates that the affected area was only 28% supported. Greed is indeed a powerful force. This was not the fault of some overactive employee trying to impress the bosses and become employee of the month, as suggested by Matt Johnson’s comment in the Big Bay meeting. Someone gave the order to widen that stope. The public needs to know who. This was an accident waiting to happen and possibly could have happened without a blast occurring and while our working neighbors and relatives were still underground,” said Champagne.

EAGLE WANTS TO TAKE MORE ORE

Prior to the collapse, Eagle Mine submitted a stability report to the MDEQ, seeking to revise the mine’s critical “Crown Pillar” design. Lundin wants to extract an additional two levels of ore from the top of the orebody. The Michigan DEQ reviewed and quietly granted their request, with no opportunity for public comment. Reports were made available only recently, after a request made by the Upper Peninsula Environmental Stakeholders Group.

Lundin Mining acknowledges in their most recent Technical Report on Eagle Mine that “due to the location of the mine under a significant wetlands area and overburden cover, a crown pillar is necessary for the Eagle Mine to prevent surface subsidence and/or large-scale collapse.” The precise thickness and strength of the mine’s “crown pillar” or rock roof has been a hotly debated issue for more than a decade. Several mining engineers, after examining drill cores and rock quality data, have concluded that Eagle Mine’s design is fundamentally unstable, based upon flawed or falsified stability data. Some stated under oath that a crown pillar less than 300 feet thick would be likely to collapse. Eagle Mine, with DEQ’s approval, has now thinned the crown pillar from 287 to only 95 feet, in order to extract more ore.

“Eagle’s secretive behavior, in the wake of the collapse, is alarming. Is Eagle Mine stable, as the company insists, or will unmapped faults prove catastrophic, as experts have warned? Nobody wants to see a serious collapse at Eagle Mine. That would devastate the headwaters of the Salmon Trout River, directly above the mine,” said Alexandra Maxwell, Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve administrator.

“No one in the Upper Peninsula should feel comfortable about the planned activities at Eagle until the financial responsibility assurances required by government regulators are at least an order of magnitude greater than what they are today,” said Loman.

“In light of last year’s significant underground collapse, which was hushed-up and passed off as a minor fall of ground incident, an independent professional review of the Eagle Mine’s data and design is needed. Ultimately, the Michigan DEQ must take steps to correct this unfortunate situation and forestall others. Mining of the Eagle East orebody must not be permitted until Eagle Mine’s design and rock data finally pass muster,” said Parker.

MORE INFO

- Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) Incident Report on Eagle Mine, 2017

- Corrected images from MSHA report (received from Chris Hensler, MSHA), 2017

- Jack Parker: Eagle Mine – Bad Design, 2017

- Lundin Mining’s Wilhelm Greuer addressing “Stability of Backfill in Secondary Stopes” transcript 2016

- Crown Pillar “Report in Support of Mine Permit Condition E8” – Golder Associates, 2016

- Mining Expert Jack Parker Says Eagle Mine “Likely To Collapse”, 2010

- Jack Parker Report Calls Eagle Project “Unstable”, 2010

- Final Report on Crown Pillar – “Stability Analysis of the Proposed Eagle Mine

Crown Pillar” – Parker and Vitton, 2007 - Technical Review — “Crown Pillar Subsidence and Hydrologic Stability Assessment for the Proposed Eagle Mine” – Sainsbury, prepared for MFG and Michigan DEQ, 2006. Excerpts:

“The analysis techniques used to assess the Eagle crown pillar stability do not reflect industry best-practice. In addition, the hydrologic stability of the crown pillar has not been considered. Therefore, the conclusions made within the Eagle Project Mining Permit Application regarding crown pillar subsidence are not considered to be defensible.”

– David Sainsbury

“A discrete sub-vertical fault plane that intersects the Eagle deposit has not been considered in any of the stability or subsidence analyses.”

– Sainsbury

“…the possibility of complete crown pillar failure should be a serious concern.”

– Sainsbury

COVERAGE

- The Mining Journal, “Group Voices Concern Over Mine Safety” June 7 2017

- WNMU-FM Public Radio 90, “Falling Rock at Eagle Mine concerns environmentalists” June 7 2017

- Dave Dempsey Books, “Torturing the Language” May 27 2017