The following is SWUP President Kathleen Heideman’s letter to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality concerning the proposed Groundwater Discharge Permit at the Eagle project.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

Permits Section

Water Resources Division

DEQ Box 30458

Lansing, MI 98909

Attention: Rick D. Rusz, Groundwater Permits Unit

Attention: Jeanette Baily, Project Coordinator

Dear Ms. Bailey and Mr. Rusz:

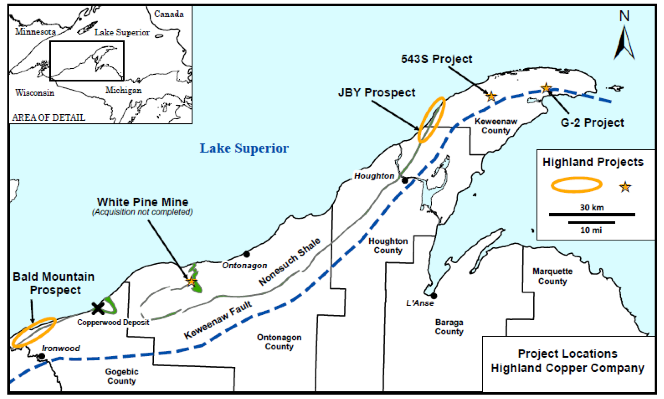

In writing this letter, I am respectfully submitting my comments to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) on the proposed revision of the groundwater discharge permit (#GW1810162) for mining wastewater discharges and other discharges, as authorized by the rapid infiltration system (TWIS) at the Eagle Mine in Marquette County, MI.

Eagle Mine, currently owned by Lundin Mining (and formerly owned by Rio Tinto) is currently permitted to construct a sulfide nickel-copper mine on the Yellow Dog Plains of Upper Michigan, with direct and indirect impacts to the Yellow Dog River Watershed, the headwaters of the Salmon Trout River, numerous groundwater-spring-fed tributaries of the Salmon Trout, and the groundwater systems underlying the Yellow Dog Plains (which remains poorly understood). The mine is publicly stating that mining operations will begin later this year.

As an adjacent landowner to Eagle Mine property, and given our reliance on several shallow wells used in our cabins, and given the presence of marshy lakes, wetlands and spring-fed ponds on our family’s lands, this groundwater discharge permit is troubling and appears deeply flawed on multiple levels — legal, regulatory, ethical, scientific and practical flaws abound.

LUNDIN MINING BEARS BURDEN OF PROOF

Regulatory oversight demands limits and enforcement. We refuse to take Eagle Mine’s “word for it” when it comes to clean water.

In applying to renew this groundwater discharge permit, which it acquired as part of the Eagle Mine purchase, Lundin Mining has the renewed burden of proving that Eagle Mine’s operations “will not pollute, impair or destroy natural resources.” Further, the Eagle facility must comply with EPA and State guidelines for water quality, specifically Michigan’s Part 632 and the Part 22 standards and statutes concerning groundwater, and MDEQ must strictly enforce those limits, and not assist the company to explain away or excuse any violations.

STRICT, CONSERVATIVE ENFORCEABLE LIMITS FOR DISCHARGED POLLUTANTS

Repeatedly, MDEQ officials and the Eagle Mine public relations team have made statements reassuring the public that this permit is just a formality, something that needs to be renewed every five years, nothing to worry about. This is insulting. A Groundwater Discharge Permit is not a document to take lightly: this is a permission slip, authorizing a global mining corporation to pollute Michigan waters UP TO any and all numeric limits set in the permit. Eagle Mine, in recent interviews and statements to the press, repeatedly downplayed the great volume of discharge authorized by this permit — HALF A MILLION GALLONS A DAY of DISCHARGED EFFLUENT — by saying they are only discharging a smaller amount at this time. MDEQ staff have also repeated this line – reminding the public that the volume of total discharges are currently lower. Nevertheless, 504,0000 gallons of daily discharges are authorized by the permit, because that is what Eagle Mine requested, based on their calculations of total expected discharges. That permitted number, half a million gallons of discharge permitted per day, remains unchanged.

What has changed? Plenty:

- Ownership of the mine has changed.

- The mine’s critical permit authorizing air pollution has been changed — to entirely eliminate pollution controls on the MVAR, which has direct impacts on groundwater and surface water quality.

- This permit includes proposed changes to the Reporting Methods which include numerous “report only” and phone call reports: this will only make it more difficult for citizens to learn about groundwater compliance problems, when violations occur, or performance issues with the mine’s WWTF. The proposed changes to reporting methods serve only to obfuscate. At the public hearing, MDEQ acknowledged that if there was a problem reported (by phone to an MDEQ staff member), “he’d make a note and put it in a file.” This is ridiculously old-fashioned and certainly not transparent. The state’s electronic systems used to report water-quality and WWTF malfunctions need to be comprehensive in scope and consistently implemented.

- This permit includes proposed changes to Effluent Limits that will degrade water quality.

- This permit includes proposed changes to the Groundwater Limits for compliance wells which will undermine water quality

- Finally, Eagle Mine suggests that the site’s “natural conditions” have changed!

MDEQ — on behalf of Lundin — is requesting increased limits due to some unspecified “natural conditions” in soils and groundwater. At the recent public hearing, anecdotally, MDEQ explained that the “new background data” is based on “data gathered between 2008 and 2011 or 2012.” No data was presented to substantiate this claim, no maps or spreadsheets containing dated sampling done by MDEQ has been shared, and there seems to be no third party water analysis or corroboration of this new “baseline” data. This request would establish a dangerous precedent: mines being permitted on the basis of one set of background data, then requesting changes to background data after the permits have been issued.

What are the actual “natural background conditions?” Compared with data from groundwater studies conducted for Rio Tinto by North Jackson, Golder Associates and TriMatrix analysis from 2004 and 2005, the new permit levels authorize exponentially MORE POLLUTION than natural background conditions actually dictate. Many of the initial levels were barely registering any level for monitored pollutants.

Some examples: most recently, in quarter 4 of 2013, chloride levels in an D-level well near the TDRSA registered more than 600 mg/L for chloride. The federal limit is 250 mg/L. By comparison, a bedrock A-level well at Eagle, tested in 2004, registered 18 mg/L for chloride. Something has changed, but it isn’t the natural soil conditions. At the hearing, MDEQ staff acknowledged that the chloride exceedances continue to be upward trending “over 700 mg/L.” And yet, MDEQ has failed to issue a single groundwater quality violation!

If anything — given the large number and recent history of exceedances for salts and metals at the Eagle facility, numeric limits need to be tightened, and the water treatment system should undergo independent certification to prove that it is working as intended. Raising the limits to match a facility’s poorer-than-expected performance is poor science, and fails to be protective of either groundwater or surface water quality.

According to Eagle Mine, we are told that “natural background conditions” have somehow changed — and that the data collected during Rio Tinto’s baseline hydrologic and geologic assessment phase was spotty, not comprehensive in scope, and now MDEQ must raise the limits to accommodate the mine’s recent exceedances, rather than adhere to limits set by the original permit. With the exception of vanadium and uranium, all constituents were defined by the mine’s initial baseline data.

Eagle project was granted their mining permit on the basis of that baseline data — groundwater data, surface water data, rock data, aquifer flow data, etc. During the contested case, the groundwater permit was presented by Kennecott, and the groundwater discharge permit was defended on the basis of that early background sampling. *IF* the baseline data used to determine Eagle Mine’s underlying assumptions about water quality and hydrogeological assessments is now deemed, in 2014, to be untrustworthy or insufficient, then the public must have no faith in the mine’s permitting process, and the mine should be formally required to get a new mining permit which includes ALL AVAILABLE NEW DATA, including water monitoring by all parties, exceedances, etc.

VIOLATIONS

When the first Groundwater Discharge Permit for Eagle Mine was being hammered out, Rio Tinto-Kennecott assured the public that they were investing in Upper Michigan for the long term, and that they shared our concern for clean water. “Your community is our community” they said. “This is where our children play, where we plan on staying for the long haul.” Rio Tinto / Kennecott has since sold the Eagle project to Lundin Mining. So much for the long term and water quality. Protecting water quality is not easy, and not cheap, but the alternative is not pretty. When our water quality is degraded by an industry, MDEQ must issue violations.

Depending on which situations are counted, exceedances related to water quality and water monitoring at the Eagle project total between 45 and 110 violations! The exceedances were not minor – in a recent cases, exceedances were more than twice the EPA’s enforceable water standards. A number of the violations had to do with pH, ironically, since this is a “world class water treatment facility” and pH treatment lies at the core of its many touted features. Effluent exceeded pH limits on multiple occasions, and in several cases they couldn’t close the valve very quickly once they realized what was happening.

Yet none of these violations has produced a single fine from the Michigan DEQ, or an independent verification of the “natural soil conditions” being blamed, or a review of the equipment being blamed at the treatment plant.

MERCURY LIMITS

Mercury testing mentions a quantification level of 0.5 ng/l unless “higher level is appropriate” due to “sample matrix interference.” Please clarify whether sample matrix interference has been calculated or anticipated? If it has not been calculated or anticipated, why not? The mine’s exemption for allowable mercury should be reconsidered in this groundwater discharge permit. How is this limit protective of surface waters, which are already impaired by mercury? Will the mine’s self-monitoring data for mercury (submitted to the MDEQ via e2-DMR) be made available for public review? Has the direct addition of mercury (air-born deposition from unfiltered MVAR-pollution) been calculated, and that total subtracted from the allowable limits, to remain protective of groundwater and surface water?

pH LIMITS

The Environmental Protection Agency has determined that drinking water should have a pH between 6.5 and 8.5 (http://www.agwt.org/content/acid-rain-and-ground-water-ph); given the Federal guidelines, the MDEQ would be irresponsible if it raised the allowable pH in Eagle’s monitoring wells. Groundwater tests in the mine area are indicating alkaline groundwater (the bonding and water-transport of heavy metals is impacted by the pH of water). Increasing the allowable limit only increases that problem. The pH limit set for compliance wells in the original groundwater discharge permit already exceeds the EPA’s range for groundwater pH.

According to A Citizen’s Guide to Understanding and Monitoring Lakes and Streams:

“Pollution may cause a long-term increase in pH. The more common concern is changes in pH caused by discharge of municipal or industrial effluents. However, most effluent pH is fairly easy to control, and all discharges in Washington State are required to have a pH between 6.0 and 9.0 standard pH units, a range that protects most aquatic life. So, although these discharges may have a measurable impact on pH, it would be unusual (except in the case of treatment plant malfunction) for pH to extend beyond the range for safety of aquatic life. However, since pH greatly influences the availability and solubility of all chemical forms in the stream, small changes in pH can have many indirect impacts on a stream.”

For this reason, increasing the pH of a discharge which shortly vents to surface waters is not protective of groundwater – and certainly not protective of surface water. A third of a mile away from the compliance wells, groundwater with a higher than natural pH could soon be emerging from the hillside, in the form of springs and spring-fed tributaries of the Salmon Trout River. Water monitoring of these streams, and the Salmon Trout River, has shown consistent surface water pH ranges between 6 and 7.5.

MDEQ limnology data from 2004 supports very low initial natural levels and a natural pH as low as 6.1 in the adjacent Salmon Trout’s headwaters. This is corroborated by data collected by Yellow Dog Watershed and USGS. Raising the groundwater discharge permit’s levels will fail to be protective of the stream’s natural pH, and aquatic stream life.

URANIUM MONITORING

Given the 2013 confirmation of uranium in waters at the Eagle Mine facility, uranium in effluent exceeding 5 ug/L will now require reporting, and some indication of the “source.” Confirming the source of the contamination — why has this not been done already? No hard evidence was made available to the public to support Eagle’s ‘uranium in imported rock’ theory.

We are reassured that the uranium is being removed during the water treatment process, along with salts and heavy metals. And yet, according to the CEMP website, the “water quality in the TDRSA and Water Treatment Plant is not regulated by the Safe Drinking Water Act. Water quality is covered under Eagle Mine’s Mine Permit and Groundwater Discharge Permit, but neither has requirements or limits for uranium. Accordingly, the detection of uranium is not a violation of any current state or federal permit.”

Given the known presence of uranium in the water at Eagle mine, the lack of concrete evidence provided by either Rio Tinto or Lundin for the uranium’s source, and public discomfort regarding the presence of a radioactive substance that could contaminate water at Eagle Mine, strict numeric limits for uranium MUST be added for groundwater monitoring.

According to an MDEQ statement: “A new standard requires monitoring for uranium in the wastewater produced by the mine. If it ever is detected at even a fraction of the safe drinking water standard, the mine must take steps to (?) reduce or eliminate the source of uranium.” Alas, “taking steps” is not an enforceable action, and it is not a measurable outcome. Reducing or eliminating the source of uranium should be tackled now, not in the future, and all wiggle-language must be removed from this permit.

The Community Environmental Monitoring Program’s announcement about uranium included this statement: “Eagle Mine BELIEVES that the detected uranium is fully contained, will be completely removed by the WTP and poses no risk to the environment.” A groundwater permit is not about BELIEF. If beliefs entered into the permitting process, my Anishnaabe friends would still be able to worship at an Eagle Rock free from fences and hard-hats and a mine portal.

Also, given that Eagle Mine assures the public and MDEQ that uranium is “completely removed by the WTP” this claim must be substantiated by a third party, and the proper “waste classification” and disposal of the WWTF/WTP’s waste products must be guaranteed as part of MDEQ’s regulatory process. It is well known that Eagle Mine’s WWTF/WTP waste is not going to the Marquette County landfill facility, which raises a lot of serious questions.

SPECIFIC CONDUCTANCE TESTING

Proposed changes — testing only for Specific Conductance — may allow the masking of significant changes in heavy metals levels within the discharged water. If the e2-DMR testing for specific conductance is CONTINUOUS and recorded daily, and submitted electronically, why would the mine be given 24 hours to “notify” the MDEQ that the effluent is outside Allowable Operational Range?

In addition, concerned citizens would like access to reporting data Eagle Mine is required to submit into the e2-DMR system.

PART 8 LIMITS

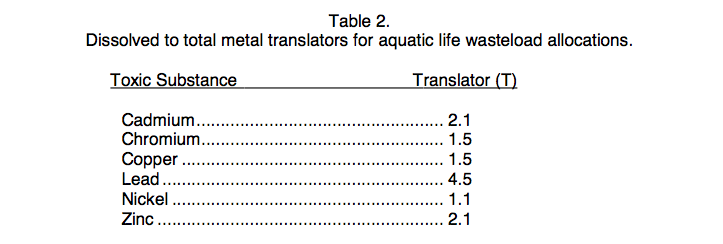

Part 8 applies to this groundwater discharge permit, as it addresses potentially toxic metals (authorized by this permit), and includes calculations and special considerations for the bioconcentration factor (BCF) and the biota-sediment accumulation factor (BSAF) of the discharge’s’ impacts on aquatic life found in surface waters. Furthermore, Part 8 specifically addresses the potential interaction between multiple toxic substances in the Eagle Mine effluent, identifying 6 critical heavy metal pollutants (cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, nickel, zinc) which function as additive pollutants and whose health/toxicity impacts (for aquatic life, and human health) must be addressed cumulatively — which MDEQ has failed to evaluate:

PART 22 LIMITS

Part 22 applies to this groundwater discharge permit, as the statute limits groundwater discharges for heavy metals, which in some cases are specifically noted as being “insufficient to protect water quality where groundwater is known to vent to surface water.”

General Conditions state that “The discharge shall not, nor not be likely to be become, injurious to the protected uses of the waters of the state”. Waters of the state of Michigan include groundwater, lakes, including Lake Superior, rivers and streams, including the Salmon Trout and its tributaries. This is clearly the situation we find at Eagle Mine. In such a case, part 22 clearly states that the standards may be tightened by lowering the discharge limits for groundwater and/or effluent, to achieve a standard protective of the surface water.

REQUESTED ACTION

1. POLLUTANT LIMITS MUST BE LOWERED, NOT RAISED

Since the first groundwater permit was issued, the underlying conditions of the environment have changed, and permit limits must be adjusted downwards to accommodate the cumulative effects: with MDEQ’s blessing, Eagle project removed the air filtration system planned for installation on the MVAR stack, in spring 2013. No filter, scrubber or bag-house now will capture the mine’s airborne pollutants, which adds a certain, calculable burden of heavy metals and other pollutants to surrounding surface waters: wetlands, streams, rivers, springs and meltwater. In addition, Eagle Mine’s air-deposited pollutants will land on the vegetation and sandy soils of the Yellow Dog Plains, and be flushed by melt/rain events into surrounding streams and wetlands. Toxic salts and heavy metals will be dissolved and carried by surface water (especially likely given the acidic nature of unfiltered air-deposited sulfide particles).

The total burden for the MVAR contamination must be calculated and then subtracted from the allowable pollution limits for Eagle’s groundwater discharges. If MDEQ’s groundwater permit fails to incorporate these known increases, surface waters would be exponentially impaired, as surface water contamination limits are so much lower.

ALL of the original projections and allowable-pollution calculations for groundwater, surface water and soils assumed that the mine’s air vent emissions would be controlled by a filter system. Given the new reality – a sulfide mine vent with no air controls, at an MVAR located a quarter mile upwind from the TWIS site — potential pollution concentrations are now underestimated by a factor of perhaps six.

Airborne pollutants — including a cocktail of chemicals, heavy metals and salts — will be increasingly deposited on the bare soils of the Eagle Mine facility and more importantly, on the lands immediately surrounding the facility, as visualized by multiple airborne dispersal diagrams, presented by MDEQ last spring. Anticipated air-deposited pollution and its impacts to flora/fauna have been previous calculated, presented to the public, and defended by the MDEQ. The proposed groundwater discharge permit fails to adhere to principles of conservatism, as it fails to include any of the expected air pollution burdens to the system; thus it does not sit on the side of sound science.

REQUESTED ACTION

2. REQUIRE TRACER FIELD

Reviewing all the original hydrogeological flow models, studies and analysis conducted by Golder, Trimatrix and North Jackson, the term “simulated” occurs repeatedly. The limited flow data gathered from well tests was run through computer simulations to determine the path that will be taken by Eagle’s groundwater discharges, how they will mix and move with groundwater, and where these discharges will emerge from the hillsides in the form of groundwater springs, feeding directly into the Salmon Trout River. These include ridiculous flow simulations that suggest a particle of groundwater will pick the most circuitous, indirect path, following ridge lines and remaining in the ground for many more miles/years than seems realistic to anyone who actually knows the hydrogeology of the Yellow Dog Plains and its terrain.

Given the lack of reliable testing concerning the path and speed of groundwater, and the dearth of monitoring wells beyond the TWIS, we still don’t know exactly when or where Eagle’s discharges, mixing with groundwater, will vent to nearby surface waters. Again, groundwater discharge permit limits must be protective of surface waters, but as the permit stands, lacking flow/path monitoring, that is impossible.

I urge the MDEQ to require Eagle Mine to install and undertake a full tracer field test for the lands surrounding Eagle Mine’s TWIS — ideally, north, northeast, east and perhaps even the southeast sides (as major concerns have been raised concerning redirection of groundwater flow as a side effect of mounding). Based on the tracer data, a set of additional groundwater compliance wells, at a correlating array of depths, should then be added to the system at the half-way point between the Eagle’s TWIS and the proven groundwater-surface water interface. No more simulations.

REQUESTED ACTION

3. REQUIRE FULL DISCLOSURE OF WWTF’s WASTE DISPOSAL

What is the total annual groundwater discharge permit fee paid by Eagle LLC for permission to pollute our groundwater resources?

Do the fees assessed for Eagle Mine appropriately reflect the volume of discharges, the risks (environmental hazards to a blue ribbon trout stream, Lake Superior, a remote area never impacted by industrial groundwater pollution), or the cost of administering and permitting the WWTF, as compared with other groundwater discharge permits issued for industries, mom-&-pop carwashes, or area laundromats? When asked directly for this information, MDEQ responds that citizens need to submit a FOIA request for the answer! This is incredibly frustrating, given that MDEQ’s public website provides other (inadequate and incomplete) information about groundwater permit fees, including the following files (which fail to mention the Eagle Mine groundwater discharge permit, or sulfide mining WWTF fees):

wb-groundwater-permits-AnnualFeeFAQ_248028_7.pdf

wb-groundwater-permitfees_248029_7.pdf

Given that the Marquette County Landfill has refused to dispose of waste products from Eagle Mine’s water treatment plant (uranium/salts issue raised the need for an expensive, lined facility), where exactly are the materials (filter cake/sludge/precipitates) being disposed of?

Michigan citizens demand to know that Eagle’s filtered materials, including uranium, are being properly disposed of, and not creating a groundwater hazard for another community that is receiving the material. Is the presence of uranium, toxic levels of heavy metals and salts in the waste properly classified, and properly disclosed at the waste’s disposal point?

During the debate over Eagle’s original mining permit included a possible scenario for disposal of sludge and WWTF wastes by entombing them within the mine, during backfill/cementing operation. Is this option still under consideration, and how will groundwater safely impacts (long-term, within saturated backfill materials) be evaluated? Will a decision to use this waste-disposal technique require a groundwater permit? Given that the public is not being notified as to the current destination of waste from the Eagle WWTF, this needs to be clarified immediately.

REQUESTED ACTION

4. PROTECTION OF THE GSI, WATERSHED DEMANDS A NPDES PERMIT

This flawed permit fails to address the certainty that the wastewater discharged at the TWIS, into the groundwater, will be emerging into groundwater-surface water interface short distance later — the permit dodges this, but MDEQ cannot dodge the issue. By failing to require Eagle Mine to get a NPDES permit to authorize and monitor the surface discharge points, the current groundwater discharge permit is authorizing an illegal discharge. A NPDES permit must be required.

REQUESTED ACTION

5. DO NOT REDEFINE THE BACKGROUND QUALITY

According to Part 22: “Background groundwater quality” means the concentration or level of a substance in groundwater within an aquifer and hydraulically connected aquifers at the site receiving a discharge, if the aquifer has not been impacted by a discharge caused by human activity. Based on the statute’s definition of background groundwater quality, one cannot accept the MDEQ’s undefined reassessment of unspecified “background data” gathered from “2008-2011” — given that exploration activities (underway in 2008), and extensive landscape changes (starting in 2009, impacting groundwater, and diverting/impounding surface waters) took place during these year. For the purposes of “background groundwater quality” no data can be included from years 2008-2012 given that the aquifer had been impacted by human activity.

According to MDEQ: “The department prepared the proposed permit after an extensive review of the mine’s wastewater treatment system, which began operation in 2011. The new permit includes minor revisions reflecting actual water conditions at the site.”

MDEQ has also stated, “Local conditions the DEQ is working to address with the renewed discharge permit include: Independent of any activity from the mine, naturally occurring background basicity and concentrations of vanadium in the groundwater exceeded the original permit standards, according to a recent assessment. Revised, site-specific limits for vanadium and pH were established in accordance with the groundwater quality administrative rules. These revised limits account for the naturally occurring conditions.”

Please explain to the public: how was the monitoring and assessment done to establish these “naturally occurring conditions”? Were any new “background wells” installed for data collection? Who conducted the data analysis? Why was the data related to this “recent assessment” not made available for concerned citizens and watersheds to independently review, prior to the permit’s extended public comment period, and/or the public hearing?

“Additionally, copper and lead levels in one well were higher than the permit allowed on three occasions, but the issue has been resolved. The well was disturbed during construction and has since been reconstructed. In the most recent sample, copper and lead levels were in compliance with the permit.”

When effluent limits are compared with surface water standards, I find that Eagle Mine’s groundwater allowable limits are consistently being set higher than what’s protective of surface water – resulting in regular exceedances that are higher than federal enforceable limits. Raising either effluent or groundwater limits to match (or nearly match) the EPA’s MCL value, will certainly not correct this problem, as exceedances are often exceeding the EPA limits!

REQUESTED ACTION

6. REEVALUATE PUBLIC ACCESS + PUBLIC IMPACTS

The public “access” to permit info and the location of the permit hearing was highly questionable. Please understand that this permit hearing was only scheduled after multiple concerned citizens lobbied MDEQ – and the initial public comment period even expired before a decision to hold the public hearing was announced. Moreover, the venue selected for the public hearing (a rural high school located west of Ishpeming, about 50 road miles from the mine itself, and 40 miles from the mine’s nearest impacted community (as defined by Part 632) — Big Bay. For the convenience of the greatest number of the public, most everyone agrees that Marquette is a far better venue choice than West Ishpeming.

Venue of the Public Hearing was a serious hardship: I’ve heard from many people who wanted to attend and could not! Many people set up carpools to reach the hearing. I personally contacted Marq-Trans (the public bus system for Marquette County) about public transit options, especially for college students who have free access to established bus routes, but learned that you’d need to ride three (3!) separate buses simply to get from downtown Marquette to downtown Ishpeming — and none of their fixed routes actually go to Westwood High School, where the permit hearing was taking place, and it didn’t really matter, because all of the busses would all quit running hours before the permit hearing would end! So — it really seems that “public access” to this “public hearing” wasn’t a serious consideration for anyone at MDEQ. That’s really unacceptable behavior for a state agency.

In addition, a “FAQs” file was initially made available online (I probably downloaded it during the month of December 2013). Reviewing info in the month leading up to the public hearing, I discovered that it referenced three other “attachments” which were not attached. When I contacted the apparent author of the FAQs file (Geri Grant, SWP, listed in the file’s “info field”) asking for these files, she contacted MDEQ and was told that these critical attachments would not be available until the night of the hearing.

WHY? — given that the FAQ sheet itself was first made available back in 2013? And why was Geri Grant listed as the author of this MDEQ file?

Why should the public have to submit FOIA requests to get basic information about groundwater permit fees? Why was the Public Hearing not listed on the MDEQ website’s calendar? The process surrounding this flawed permit has been repeatedly dismissive of the public’s right to know, and right to participate. MDEQ owes it to the citizens of Michigan’s U.P. to do better.

“The less information available to the public about the full range of impacts from the proposed mine and the less time and opportunity for the public to counter the false claims of the mining company, the better the chances of permitting.” – Al Gedicks

If you have any questions regarding my criticisms, comments, or requested actions, please do not hesitate to contact me at president@savethewildup.org or by mail:

224 Riverside Road, Marquette MI 49855.

Sincerely,

Kathleen M. Heideman

President, Save the Wild U.P.