FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Big Holes in Mining Exploration Regulations?

MARQUETTE — Lundin Mining, parent company of Eagle Mine, recently announced exploration results for the orebody known as “Eagle East,” which is located outside the current footprint of the mine and said to contain “high grade massive and semi-massive copper-nickel sulfide mineralization.” With the current Eagle orebody located just below the Salmon Trout River and “Eagle East” exploration approaching the Yellow Dog River, environmental groups are speaking out about renewed concerns regarding ground and surface water contamination, the creeping industrialization of the Yellow Dog Plains, undisclosed exploratory drilling, trash left by exploration contractors, and the threat posed by acid mine drainage (AMD).

AMD is a dangerous byproduct of sulfide mining. Sought-after minerals such as copper, nickel, lead, cobalt, silver and zinc are embedded in sulfides; the process of extraction brings the sulfide-rich rock into contact with air and water, resulting in sulfuric acid. AMD could devastate watersheds like the Salmon Trout or the Yellow Dog, as it has historically devastated watersheds in coal mining regions, and in hardrock mining districts throughout the Rocky Mountains.

In Michigan, mineral exploration is regulated under Part 625, which establishes the protocol for adherence to environmental protections during the exploration phase. According to the state’s “Typical Metallic Mining Exploration Flowchart,” much of the mineral exploration process occurs before any permits are required, allowing industry to perform much of the exploration process without regulatory or public scrutiny.

Companies currently conducting exploratory drilling on the Yellow Dog Plains do so with impunity. According to the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), “(E)xploration companies are extremely secretive about their projects. All information regarding exploration drilling is considered proprietary under Part 625.” According to the MDEQ, “Most metallic mineral exploration occurs in an area exempt from acquiring a Part 625 permit.”

The lack of oversight has real consequences. Following a phase of surface and seismic mineral exploration in 2014, performed by Lundin Mining contractors who pulled miles of geophysical survey cables through the landscape, piles of PVC pipes were left abandoned in forests, ravines, and swamps, a plague of plastic ribbons fluttered from trees, and ATV tracks cut through wetlands.. Members of the public – including adjacent landowners and and watersheds – learn of exploration drilling sites only when the drill rigs appear, bringing 24-hour drilling noise, or leaving behind pools of drilling fluid.

“Given the new Wild West mining camp vibe, who is monitoring the work of Lundin’s numerous contractors?” asked Alexandra Maxwell, Save the Wild U.P. interim director. “What enforcement tools are in place to guarantee adherence to environmental safeguards, as specified under Part 625? Is anyone really checking the situation on the ground? It appears that Lundin’s contractors don’t even pick up their trash when they finish a project.”

While Lundin is quick to promote the potential “Eagle East” discovery to its investors, they insist that it is too soon to consider any environmental concerns. Eagle Mine’s spokesman Dan Blondeau has stated, “We’re very early in the exploration stage for this area. It’s too early to tell if this will materialize into anything significant. It’s too early to talk mining or permitting.” According to the MDEQ’s mineral exploration flowchart, however, drilling is actually one of the final stages of exploration.

According to Kathleen Heideman, SWUP president, “Lundin’s new orebody appears to be comprised of copper-nickel-platinum-palladium, all wrapped in a matrix of massive hype. Investors, beware! No word on how much uranium-vanadium-arsenic this orebody will contain — but the Yellow Dog River will be directly threatened. This is nothing to celebrate.”

“If mined, this orebody puts Lundin in a position to contaminate the Yellow Dog River. Rio Tinto had made a big public relations effort to assure citizens that their mining was going to leave a small footprint and would NOT contaminate the Yellow Dog River watershed — just the Salmon Trout River. Now by “discovering” a so-called new deposit they are incrementally expanding their footprint and clearly violating their promises,” said Michael Loukinen, SWUP advisory board member, filmmaker, and retired professor of Sociology at Northern Michigan University. “I fear that this will not be the first discovery of new deposits but the beginning of a pattern of new environmental losses.”

“In 2004, the Yellow Dog Watershed Preserve (YDWP), Concerned Citizens of Big Bay, all but one of the townships of Marquette County, and the Marquette County Commission petitioned the State of Michigan to require that a full Hydrologic Assessment of the Yellow Dog Plains be done, by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) — *before* any mining activities took place on the Plains. That did not happen,” said Cynthia Pryor,YDWP board member. Now, more than ever, there needs to be a third party hydrologic assessment of the Plains and the only party qualified to do an unbiased assessment is the USGS. They are already involved in surface water monitoring on the Plains, so let them do their job and give us, the people of the State of Michigan, the straight story about the cumulative impact of these sulfide metallic mines on the Yellow Dog Plains.”

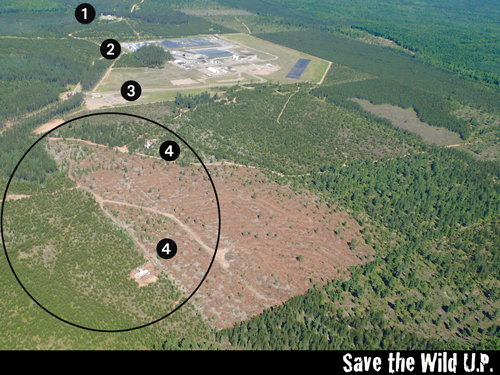

Eagle Mine’s environmental impacts continue to expand. Aerial photograph taken on June 19, 2015 shows: 1. Salmon Trout River, Eagle orebody and Main Vent Air Raise, 2. Eagle Rock and mining portal tunnel, 3. Eagle Mine surface facility, and 4. new drilling rigs, logging and mineral exploration in what Lundin is calling the “Eagle East” area.

“This is by-the-book mining boom hype,” said Heideman. “Mining companies create a bunch of hullabaloo about their ‘discoveries’ years before a permit is negotiated, or a single dollar of ore is removed from the ground. Meanwhile, the mining company will be working hard to extract big dollars from investors — at the expense of the wild Upper Peninsula.”

“The mine’s industrial wastewater discharges at Eagle mine are presenting to the surface,” said Jeffery Loman, former federal oil regulator. “Soon there will be undisputed evidence that Lundin is violating the Clean Water Act. When people across the U.P. finally realize our water is at risk, Eagle East will go South.”

Founded in 2004, Save the Wild U.P. is a grassroots environmental organization dedicated to preserving the Upper Peninsula of Michigan’s unique cultural and environmental resources. For more information contact info@savethewildup.org or call (906) 662-9987. Get involved with SWUP’s work at savethewildup.org or follow SWUP on Facebook at facebook.com/savethewildup or Twitter @savethewildup.

Editors: the following photos are available for use with this press release.

Aerial photograph showing Eagle East mineral exploration footprint

Sizes available: 1500 px wide or original, 4608 px wide

Suggested caption: “Eagle Mine’s environmental impacts continue to expand. Aerial photograph taken on June 19, 2015 shows: 1. Salmon Trout River, Eagle orebody and Main Vent Air Raise, 2. Eagle Rock and mining portal tunnel, 3. Eagle Mine surface facility, and 4. new drilling rigs, logging and mineral exploration in what Lundin is calling the “Eagle East” area.”

Trashing the Yellow Dog Plains

Eagle Mine TWIS blue styrofoam (windblown trash)

Lundin Mining exploration trash: PVC pipes (view 1)

Lundin Mining exploration trash: PVC pipes (view 2)

Lundin Mining exploration trash: PVC pipes (view 3)

Mining exploration trash left in ravines (view 4)

Mining exploration trash left in ravines (view 5)

Yellow Dog Plains: drilling oil in sand pit (Kennecott). Photo courtesy of Shawn Malone/ LakeSuperiorPhoto

- Eagle East

- Chunks of blue board styrofoam, apparently used to cover the site where Eagle Mine discharges its industrial wastewater, have blown into adjacent State Forest land on the Yellow Dog Plains.

- White trash: PVC pipes used by Eagle Mine’s contractors during 2014 mineral exploration were abandoned in woods, swamps and ravines of the Yellow Dog Plains.

- White trash: PVC pipes used by Eagle Mine’s contractors during 2014 mineral exploration were abandoned in woods, swamps and ravines of the Yellow Dog Plains.

- White trash: PVC pipes used by Eagle Mine’s contractors during mineral exploration are being found abandoned in woods, swamps and ravines of the Yellow Dog Plains.

- White trash: PVC pipes used by Eagle Mine’s contractors during mineral exploration are being found abandoned in woods, swamps and ravines of the Yellow Dog Plains.

- White trash: PVC pipes used by Eagle Mine’s contractors during 2014 mineral exploration are being found abandoned in woods, swamps and ravines of the Yellow Dog Plains.

- Early exploration by Kennecott; photograph courtesy of Shawn Malone/ Lake Superior Photo.